Transform Your Workflow with Scry AI Automation

Get StartedDuring the last decade, India has witnessed tremendous growth, recording a growth rate of 8-9% annually.

With rising income and education levels as well as a young workforce, the aspirations of the common man

have also increased. The Indian middle class, estimated to be 300 million people [1], has become more

status conscious. A recent study by Neilson found India to be among the top three brand conscious

countries in the world [2]. Clearly, the Indian consumer is no longer satisfied with – or loyal to – the old and familiar, but is rather looking for new and better alternatives.

The Indian consumer’s preference for foreign brands over local ones is putting pressure on the domestic

industry to innovate and differentiate itself in the marketplace. Globalization has created additional

challenges. Given these trends, it has become imperative for the Indian Government to become more

serious about promoting and protecting innovation.

Traditional means of protecting and promoting innovation have proven inadequate for India. Introducing

utility models protection will be a quicker, cheaper and easier mode of achieving protectionmanner. In our

view, the answer lies in the Indian Patent Office allowing the grant of utility model patents. Typically, utility models are awarded for new technical solutions that relate to a product’s shape or structure, or a

combination of the two, and are also fit for practical use. They are usually awarded for ten years and since

they do not involve any substantive examination, we believe that the Indian Patent Office can award them

within six months after being filed and charge a fee of 4,000 Indian Rupees so that the total cost to the

inventor for each utility model patent is no more than 9,000 Indian Rupees. Finally, we think that the

recognition potential of utility model patents (and their associated ‘status’ quotient) can revolutionize the domestic industry by creating an innovation culture and making the domestic industry substantially more

competitive.

India currently has more than 1,500 engineering institutions that graduate more than 500,000 students every

year [3]. Although India may have more engineers than the entire population of some developed countries,

innovation is relatively non-existent and not as recognized as it should be.

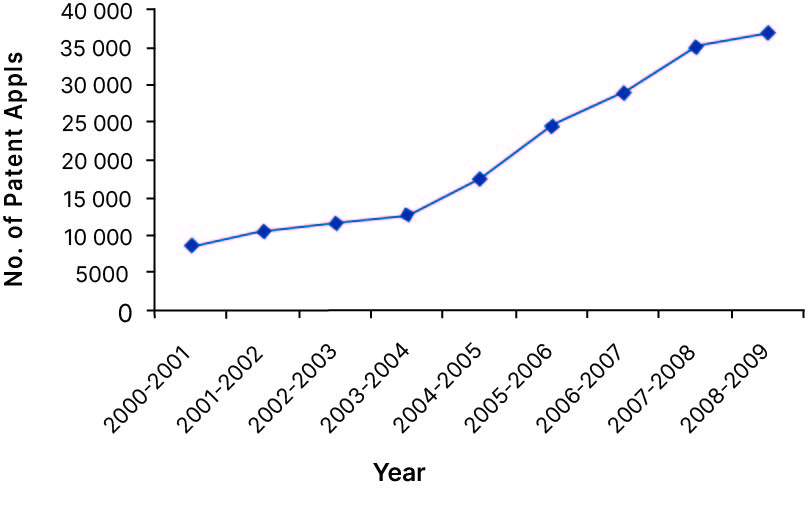

The number of patent applications filed per year is a good metric of measuring the innovation potential of a

country. In this regard, India fares quite poorly when compared to many other developed and developing

countries. Figure 1 given below illustrates the growth in the number of patent applications that have been

filed with the Indian patent office (IPO) during the last few years.

While the US, Japan and China recorded more than 300,000 patent applications each in the year 2009,

India had only 35,000. Although these statistics may be an indication of a lack of scientific innovation, they can also be attributed to the fact that Indians are generally not enthusiastic about patenting their innovations.

Patents are one of the best modes of recognizing innovation because not only do they declare the rightful

owner of an invention (by making it public knowledge), they also provide an opportunity for the inventor to

profit from the invention, and for others to improve it. Investors seeking to develop grass-root innovation can easily identify and analyse inventions through publicly available patents, whereas, inventors can get instant recognition and a boost to their morale, which can further stimulate their enthusiasm in developing new technologies. Furthermore, patents also serve as important certificates of achievement for scientists and researchers. It is not surprising that Abraham Lincoln, the only United States President to ever receive a patent, once declared that patent law added the fuel of interest to the fire of genius.

Interestingly, one of the recent blockbuster movies from Bollywood, ‘3 Idiots’, showcased some real-life

inventions (e.g., cycle pedal powered sheep fleecing device, scooter engine powered grinding machine),

which are often called grass-root innovations since they were not invented in big research and development

(R&D) laboratories. Such grass-root innovations are an indication that there is an innovative capacity waiting

to be tapped – not just only in the research labs, but also in the hinterlands of India. The National Innovation

Foundation, an initiative of the Government of India, has identified more than 140,000 grass root innovations

[4]; however, to date, less than 300 patent applications have been filed by this foundation [5].

Why is there a general lack of patenting in India? The answer may lie in the lack of awareness. Not only

grass-root innovators, even business owners, R&D scientists, engineers and many professors are unaware

of the power of owning patents. A popular perception in India is that patents are instruments used only by

profit-minded corporations for their own benefit and they ignore the needs of the population at large.

Although the Indian Patent Office and the government are making efforts to create better awareness and

multi-national companies are becoming role models in patenting, these efforts have been stymied by the

enormous cost and time spent during the entire patenting process. As the general awareness for Intellectual

Property (IP) rights grows, the IP protection system and processes also come into focus. There is a need for

a quicker, cheaper and easier means of achieving patent protection, and in our view, the answer lies in the

Indian Patent Office granting utility model patents. Utility models have been successful in boosting domestic

industries in 75 countries. Many developed countries (e.g., Germany and Australia) as well as developing

ones (e.g., China and Brazil) already allow the grant of Utility models. One country that has done remarkably

well in this regard is China.

China opened its economy in 1978, and in 1985 it established its patent law that has since undergone three

rounds of amendments. The most recent amendments became effective in October 1, 2009. All these

amendments have made the Chinese patent law similar to those in many other countries. Through the years,

China also became a signatory to international treaties like the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) and

agreements like the Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement. Since the

establishment of its patent law 26 years ago, the Chinese government has realized the importance of

Intellectual Property (IP) protection, and has therefore developed a comprehensive legislation and set of

institutions that are responsible for patent examination and enforcement. In our paper titled ‘Patenting

Landscape in China’ that was published in 2008 [6], we showed how the Chinese patent system has evolved

during the last two decades.

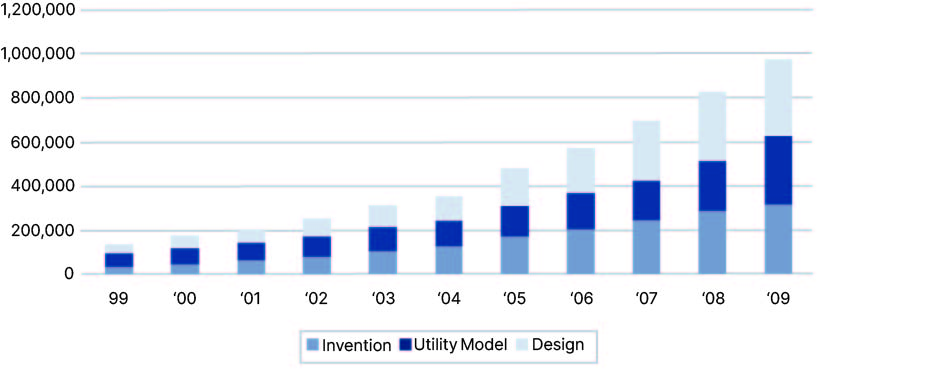

The Chinese patent regime is relatively young compared to that in other countries. However, China has

developed its patent system at an astonishing rate to become one of the largest patent filing jurisdictions in

the world. A key feature of the Chinese patent system is the availability of three different kinds of patents:

invention patents (20-year patents), utility model patents (10-year patents), and design patents. In the year

2009, the State Intellectual Property Office (SIPO) of China recorded close to a million patent applications, which included 314,573 invention patent applications (i.e., 20-year applications), 310,771 utility model

applications (i.e., 10-year applications) and 351,342 design patent applications. The growth in patent

application filing in China is illustrated in Figure 2 below.

It is quite remarkable that China has achieved such growth within 26 years of establishing its patent law.

What is even more remarkable is that a majority of these patent applications were filed by domestic

applicants. In the year 2009, 72% of 20-year applications filed in China were filed by Chinese applicants,

whereas less than 20% of applications were filed in India by Indian applicants [7].

Table 1 below compares Indian and Chinese patent systems with respect to a few parameters. Interestingly,

the situation in India in 2009 was somewhat similar to that of China in 1999. The growth of the Chinese

economy is an obvious reason for the growth in patent filing activity. However, if the economic growth were

the only factor, then India should also have seen a faster growth in the number of patent applications

because the Indian economy has also been growing steadily during the past few years. It is clear that at

least one other factor has significantly contributed to the growth in the patent filing numbers in China, and

this is the Chinese patent system allowing the granting of utility models or 10-year patents. In 1999, only

42.5% of the invention patent applications were filed by domestic applicants, whereas 99.5% of the utility

model applications were filed by domestic applicants. In the year 2009, the share of domestic applicants

filing invention patent applications grew to 72%, whereas the share filing utility model applications remained

almost the same at 99.2%. Clearly, domestic Chinese companies are keen to file utility models and they

have played an important role in increasing the awareness among Chinese organizations towards

intellectual property and particularly, the patenting system. It is important to study the utility model system

and examine how the utility models can be beneficial to the Indian patent system.

| Table 1: Comparison of Indian and Chinese patent systems (for 20-year applications) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| India – 2008-09 | China – 2009 | China – 1999 | |

| Total no. of 20-year | 36,877 | 314,573 | 36,694 |

| Share of domestic applicants | Less than 20% | 72% | 42.5% |

| Full-text of patents available online for free | No | Yes. All patents and published applications available online | No |

| Utility Model protection | No | Yes | Yes |

| Available | |||

| Source: Publications of the Indian Patent Office and the State Intellectual Property Office (SIPO) of PR China | |||

Utility models have existed for more than two decades in China. They recently garnered additional attention,

because of their sheer volume; the success of the Chint group in asserting its utility model against Schneider

Electric also drew considerable attention on the subject. The Chint group, a Chinese manufacturer, sued

Schneider, a French multinational, for infringement of its utility model. The Wenzhou Intermediate People’s

Court decided in favour of the Chint group and awarded it enormous damages (worth approx. USD 45

million). Schneider eventually settled for USD 23 million, which may still have been a record for any patent litigation in China. The Chint vs. Schneider case illustrates the importance of utility models in the present-

day business scenario. In addition to China, a number of other countries (e.g., Germany, Japan, Australia, South Korea, and Brazil) award utility models as an alternative mode for patent protection. It is, therefore,

important to understand how these utility models are different from invention patents. Table 2 below

provides a comparison.

| Table 2: Comparison of Chinese Invention Patents and Utility Models | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Invention patents | Utility Models | ||

| Awarded for | New technical solutions that relate to a product, a process or an improvement thereof |

New technical solutions that relate to a product’s shape or structure, or a combination of the two, and are also fit for practical use |

|

| Term of protection | 20 years from the filing date | 10 years from the filing date | |

| Conditions that bar patentability | *Prior public disclosure * Prior public knowledge or use * Lack of novelty * Lack of inventiveness * Cannot be made or used, and cannot produce effective results |

*Prior public disclosure * Prior public knowledge or use * Lack of novelty * Lack of inventiveness * Cannot be made or used, and cannot produce effective results |

|

| Request for substantive examination | Within 3 years of the filing date | No need for substantive examination | |

| Time to grant | 3 to 5 years | A utility model is typically granted within a year of the application being filed |

|

| Fees | Application and publication fees: Chinese Yuan 950 Substantive examination fee: Chinese Yuan 2,500 Re-examination fee: Chinese Yuan 1,000 |

Application and publication fees: Chinese Yuan 500 Substantive examination fee: NONE Re-examination fee: Chinese Yuan 300 |

|

| Source: The State Intellectual Property Office of China | |||

Although all the legal attributes that are available to the invention patents (i.e., 20-year patents) are also available to utility models (i.e., 10-year patents), utility models differ from invention patents in the following respects:

a). there is no substantive examination leading to a quick grant

b). the life of utility models is only ten years, and

c). application, examination, maintenance, and attorney fees are substantially lower

Simply put, utility models are cheaper, easier and quicker to obtain than invention patents.

Much like China, a cheaper and easier mode of obtaining patent protection will also have benefits in the

Indian context:

Of course, the acceptance of utility models does not imply that they would replace invention patents,

especially because utility models have a few limitations also.

Given below are some perceived disadvantages of utility patents and a few potential solutions for mitigating

these:

Criticism 1: Utility Models are ‘Junk’ patents:

The lack of substantive examination may allow patents to be granted for inventions that may not be patented

otherwise. This may lead to an unnecessary increase in the number of applications as well as the number of

granted utility patents.

Potential solution: Post-grant opposition should be available via an administrative process at the Indian Patent Office, which can be used to proactively invalidate utility models that are not novel. While the utility models are published by the patent office to recognize new inventions, such publication will also open them up for public scrutiny. This will also help in making the entire process transparent. Furthermore, the invention categories that will be excluded from the scope of utility model protection should be clearly defined before allowing utility model applications. For example, inventions related to chemicals, pharmaceuticals, biological material or substances or processes may be excluded from utility model protection. The aim for utility models is to help small enterprises and grass-root innovators to protect simple and incremental innovations, whereas the traditional patent route would be a better route for protecting complex innovations.

Criticism 2: Utility models cause an increase in unnecessary litigation:

Since utility models are not substantively examined, unnecessary litigation may increase because many

utility models may not be novel to begin with. In the worst possible scenario, a counterfeiting company can

obtain a utility model for an existing, but not well-known technology and sue the actual owner of that

technology. Such situations may put additional burden on the courts and the patent office due to a sharp

increase in false litigation suits (in courts) and requests for invalidation requests (at the Indian patent office).

Potential solution: For any utility model, a prior art search report should be made mandatory before any

litigation can proceed. Such a search report will help in identifying the novelty and non-obviousness of the

invention, thereby preventing false litigation and making it easier to invalidate utility models that do not

contain any novelty. The burden for creating the search reports should be moved from the patent office to

the owner of the utility model or the person involved in invalidating it. The utility model holder must request

and pay for a search report before enforcing it in an infringement suit. Similarly, a person interested in

invalidating the utility model must request and pay for the search report from the patent office.

Criticism 3: Utility models have too short a term:

Utility models have a ten-year term, which is half of the term for invention patents. This may seem short for some inventions, e.g., pharmaceutical drugs that need to go through multiple rounds of clinical trials.Utility models have a ten-year term, which is half of the term for invention patents. This may seem short for some inventions, e.g., pharmaceutical drugs that need to go through multiple rounds of clinical trials.

Potential solution: Utility models should probably not cover pharmaceutical drugs or similar inventions. Utility

models are a boon for technologies that have a much shorter life span. Further, the provision of a yearly

maintenance fee will ensure that utility models for technologies that are no longer of interest are unlikely to be maintained for a long time. For example, the minimum term of granted utility models may be as small as

four years, which can be extended to seven years, and then ten years by paying small fees. The renewal fee

will help in weeding out unused utility model and in reducing the ‘junk’ utility models.

Criticism 4: Utility models put an unnecessary strain on the patent office:

If applications for utility models are allowed, the patent office will be even busier and would be distracted from working on invention patent applications and other activities.

Possible solution: A fast examination system should be implemented, wherein the patent office only examines a utility model application for completeness (e.g., application in prescribed format, the invention described completely). The patent office should avoid substantive examination with respect to novelty.

Finally, several research papers have highlighted the benefits of utility models for developing countries like India. For example, one article has been published by International Centre for Trade and Sustainable

Development (ICTSD) and United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), [8]; it

suggests various measures to implement an ideal utility model system.

The Indian government needs to seriously think about adopting utility model protection as a supplementary

form of patent protection. Despite impressive economic growth during the last two decades, the level of

innovation and Intellectual Property Rights generated and held by Indian domestic companies remains low,

reflecting the fact that the patent system in India is inadequate for boosting innovation. Given the ‘status

conscious’ Indian psyche, utility models are more likely to be successful than invention patents. Furthermore, they will give a much needed push to the domestic sector by putting it at par with their foreign counterparts in terms of innovation culture and competitiveness. In this regard, India can learn from the Chinese experience and can have the right checks and balances to implement a better patenting regime.

In summary, the relevance and advantages of utility models in India outweigh their limitations and

disadvantages. Utility model protection has proved to be popular and successful in more than 75 countries,

and we strongly believe that if implemented properly in India, it will do more good than harm.

At Scry Analytics Inc ("us", "we", "our" or the "Company") we value your privacy and the importance of safeguarding your data. This Privacy Policy (the "Policy") describes our privacy practices for the activities set out below. As per your rights, we inform you how we collect, store, access, and otherwise process information relating to individuals. In this Policy, personal data (“Personal Data”) refers to any information that on its own, or in combination with other available information, can identify an individual.

We are committed to protecting your privacy in accordance with the highest level of privacy regulation. As such, we follow the obligations under the below regulations:

This policy applies to the Scry Analytics, Inc. websites, domains, applications, services, and products.

This Policy does not apply to third-party applications, websites, products, services or platforms that may be accessed through (non-) links that we may provide to you. These sites are owned and operated independently from us, and they have their own separate privacy and data collection practices. Any Personal Data that you provide to these websites will be governed by the third-party’s own privacy policy. We cannot accept liability for the actions or policies of these independent sites, and we are not responsible for the content or privacy practices of such sites.

This Policy applies when you interact with us by doing any of the following:

What Personal Data We Collect

When attempt to contact us or make a purchase, we collect the following types of Personal Data:

This includes:

Account Information such as your name, email address, and password

Automated technologies or interactions: As you interact with our website, we may automatically collect the following types of data (all as described above): Device Data about your equipment, Usage Data about your browsing actions and patterns, and Contact Data where tasks carried out via our website remain uncompleted, such as incomplete orders or abandoned baskets. We collect this data by using cookies, server logs and other similar technologies. Please see our Cookie section (below) for further details.

If you provide us, or our service providers, with any Personal Data relating to other individuals, you represent that you have the authority to do so and acknowledge that it will be used in accordance with this Policy. If you believe that your Personal Data has been provided to us improperly, or to otherwise exercise your rights relating to your Personal Data, please contact us by using the information set out in the “Contact us” section below.

When you visit a Scry Analytics, Inc. website, we automatically collect and store information about your visit using browser cookies (files which are sent by us to your computer), or similar technology. You can instruct your browser to refuse all cookies or to indicate when a cookie is being sent. The Help Feature on most browsers will provide information on how to accept cookies, disable cookies or to notify you when receiving a new cookie. If you do not accept cookies, you may not be able to use some features of our Service and we recommend that you leave them turned on.

We also process information when you use our services and products. This information may include:

We may receive your Personal Data from third parties such as companies subscribing to Scry Analytics, Inc. services, partners and other sources. This Personal Data is not collected by us but by a third party and is subject to the relevant third party’s own separate privacy and data collection policies. We do not have any control or input on how your Personal Data is handled by third parties. As always, you have the right to review and rectify this information. If you have any questions you should first contact the relevant third party for further information about your Personal Data.

Our websites and services may contain links to other websites, applications and services maintained by third parties. The information practices of such other services, or of social media networks that host our branded social media pages, are governed by third parties’ privacy statements, which you should review to better understand those third parties’ privacy practices.

We collect and use your Personal Data with your consent to provide, maintain, and develop our products and services and understand how to improve them.

These purposes include:

Where we process your Personal Data to provide a product or service, we do so because it is necessary to perform contractual obligations. All of the above processing is necessary in our legitimate interests to provide products and services and to maintain our relationship with you and to protect our business for example against fraud. Consent will be required to initiate services with you. New consent will be required if any changes are made to the type of data collected. Within our contract, if you fail to provide consent, some services may not be available to you.

Where possible, we store and process data on servers within the general geographical region where you reside (note: this may not be within the country in which you reside). Your Personal Data may also be transferred to, and maintained on, servers residing outside of your state, province, country or other governmental jurisdiction where the data laws may differ from those in your jurisdiction. We will take appropriate steps to ensure that your Personal Data is treated securely and in accordance with this Policy as well as applicable data protection law.Data may be kept in other countries that are considered adequate under your laws.

We will share your Personal Data with third parties only in the ways set out in this Policy or set out at the point when the Personal Data is collected.

We also use Google Analytics to help us understand how our customers use the site. You can read more about how Google uses your Personal Data here: Google Privacy Policy

You can also opt-out of Google Analytics here: https://tools.google.com/dlpage/gaoptout

We may use or disclose your Personal Data in order to comply with a legal obligation, in connection with a request from a public or government authority, or in connection with court or tribunal proceedings, to prevent loss of life or injury, or to protect our rights or property. Where possible and practical to do so, we will tell you in advance of such disclosure.

We may use a third party service provider, independent contractors, agencies, or consultants to deliver and help us improve our products and services. We may share your Personal Data with marketing agencies, database service providers, backup and disaster recovery service providers, email service providers and others but only to maintain and improve our products and services. For further information on the recipients of your Personal Data, please contact us by using the information in the “Contacting us” section below.

A cookie is a small file with information that your browser stores on your device. Information in this file is typically shared with the owner of the site in addition to potential partners and third parties to that business. The collection of this information may be used in the function of the site and/or to improve your experience.

To give you the best experience possible, we use the following types of cookies: Strictly Necessary. As a web application, we require certain necessary cookies to run our service.

We use preference cookies to help us remember the way you like to use our service. Some cookies are used to personalize content and present you with a tailored experience. For example, location could be used to give you services and offers in your area. Analytics. We collect analytics about the types of people who visit our site to improve our service and product.

So long as the cookie is not strictly necessary, you may opt in or out of cookie use at any time. To alter the way in which we collect information from you, visit our Cookie Manager.

A cookie is a small file with information that your browser stores on your device. Information in this file is typically shared with the owner of the site in addition to potential partners and third parties to that business. The collection of this information may be used in the function of the site and/or to improve your experience.

So long as the cookie is not strictly necessary, you may opt in or out of cookie use at any time. To alter the way in which we collect information from you, visit our Cookie Manager.

We will only retain your Personal Data for as long as necessary for the purpose for which that data was collected and to the extent required by applicable law. When we no longer need Personal Data, we will remove it from our systems and/or take steps to anonymize it.

If we are involved in a merger, acquisition or asset sale, your personal information may be transferred. We will provide notice before your personal information is transferred and becomes subject to a different Privacy Policy. Under certain circumstances, we may be required to disclose your personal information if required to do so by law or in response to valid requests by public authorities (e.g. a court or a government agency).

We have appropriate organizational safeguards and security measures in place to protect your Personal Data from being accidentally lost, used or accessed in an unauthorized way, altered or disclosed. The communication between your browser and our website uses a secure encrypted connection wherever your Personal Data is involved. We require any third party who is contracted to process your Personal Data on our behalf to have security measures in place to protect your data and to treat such data in accordance with the law. In the unfortunate event of a Personal Data breach, we will notify you and any applicable regulator when we are legally required to do so.

We do not knowingly collect Personal Data from children under the age of 18 Years.

Depending on your geographical location and citizenship, your rights are subject to local data privacy regulations. These rights may include:

Right to Access (PIPEDA, GDPR Article 15, CCPA/CPRA, CPA, VCDPA, CTDPA, UCPA, LGPD, POPIA)

You have the right to learn whether we are processing your Personal Data and to request a copy of the Personal Data we are processing about you.

Right to Rectification (PIPEDA, GDPR Article 16, CPRA, CPA, VCDPA, CTDPA, LGPD, POPIA)

You have the right to have incomplete or inaccurate Personal Data that we process about you rectified.

Right to be Forgotten (right to erasure) (GDPR Article 17, CCPA/CPRA, CPA, VCDPA, CTDPA, UCPA, LGPD, POPIA)

You have the right to request that we delete Personal Data that we process about you, unless we need to retain such data in order to comply with a legal obligation or to establish, exercise or defend legal claims.

Right to Restriction of Processing (GDPR Article 18, LGPD)

You have the right to restrict our processing of your Personal Data under certain circumstances. In this case, we will not process your Data for any purpose other than storing it.

Right to Portability (PIPEDA, GDPR Article 20, LGPD)

You have the right to obtain Personal Data we hold about you, in a structured, electronic format, and to transmit such Personal Data to another data controller, where this is (a) Personal Data which you have provided to us, and (b) if we are processing that data on the basis of your consent or to perform a contract with you or the third party that subscribes to services.

Right to Opt Out (CPRA, CPA, VCDPA, CTDPA, UCPA)

You have the right to opt out of the processing of your Personal Data for purposes of: (1) Targeted advertising; (2) The sale of Personal Data; and/or (3) Profiling in furtherance of decisions that produce legal or similarly significant effects concerning you. Under CPRA, you have the right to opt out of the sharing of your Personal Data to third parties and our use and disclosure of your Sensitive Personal Data to uses necessary to provide the products and services reasonably expected by you.

Right to Objection (GDPR Article 21, LGPD, POPIA)

Where the legal justification for our processing of your Personal Data is our legitimate interest, you have the right to object to such processing on grounds relating to your particular situation. We will abide by your request unless we have compelling legitimate grounds for processing which override your interests and rights, or if we need to continue to process the Personal Data for the establishment, exercise or defense of a legal claim.

Nondiscrimination and nonretaliation (CCPA/CPRA, CPA, VCDPA, CTDPA, UCPA)

You have the right not to be denied service or have an altered experience for exercising your rights.

File an Appeal (CPA, VCDPA, CTDPA)

You have the right to file an appeal based on our response to you exercising any of these rights. In the event you disagree with how we resolved the appeal, you have the right to contact the attorney general located here:

If you are based in Colorado, please visit this website to file a complaint. If you are based in Virginia, please visit this website to file a complaint. If you are based in Connecticut, please visit this website to file a complaint.

File a Complaint (GDPR Article 77, LGPD, POPIA)

You have the right to bring a claim before their competent data protection authority. If you are based in the EEA, please visit this website (http://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/article29/document.cfm?action=display&doc_id=50061) for a list of local data protection authorities.

If you have consented to our processing of your Personal Data, you have the right to withdraw your consent at any time, free of charge, such as where you wish to opt out from marketing messages that you receive from us. If you wish to withdraw your consent, please contact us using the information found at the bottom of this page.

You can make a request to exercise any of these rights in relation to your Personal Data by sending the request to our privacy team by using the form below.

For your own privacy and security, at our discretion, we may require you to prove your identity before providing the requested information.

We may modify this Policy at any time. If we make changes to this Policy then we will post an updated version of this Policy at this website. When using our services, you will be asked to review and accept our Privacy Policy. In this manner, we may record your acceptance and notify you of any future changes to this Policy.

To request a copy for your information, unsubscribe from our email list, request for your data to be deleted, or ask a question about your data privacy, we've made the process simple:

Our aim is to keep this Agreement as readable as possible, but in some cases for legal reasons, some of the language is required "legalese".

These terms of service are entered into by and between You and Scry Analytics, Inc., ("Company," "we," "our," or "us"). The following terms and conditions, together with any documents they expressly incorporate by reference (collectively "Terms of Service"), govern your access to and use of www.scryai.com, including any content, functionality, and services offered on or through www.scryai.com (the "Website").

Please read the Terms of Service carefully before you start to use the Website.

By using the Website [or by clicking to accept or agree to the Terms of Service when this option is made available to you], you accept and agree to be bound and abide by these Terms of Service and our Privacy Policy, found at Privacy Policy, incorporated herein by reference. If you do not want to agree to these Terms of Service, you must not access or use the Website.

Accept and agree to be bound and comply with these terms of service. You represent and warrant that you are the legal age of majority under applicable law to form a binding contract with us and, you agree if you access the website from a jurisdiction where it is not permitted, you do so at your own risk.

We may revise and update these Terms of Service from time to time in our sole discretion. All changes are effective immediately when we post them and apply to all access to and use of the Website thereafter.

Continuing to use the Website following the posting of revised Terms of Service means that you accept and agree to the changes. You are expected to check this page each time you access this Website so you are aware of any changes, as they are binding on you.

You are required to ensure that all persons who access the Website are aware of this Agreement and comply with it. It is a condition of your use of the Website that all the information you provide on the Website is correct, current, and complete.

You are solely and entirely responsible for your use of the website and your computer, internet and data security.

You may use the Website only for lawful purposes and in accordance with these Terms of Service. You agree not to use the Website:

The Website and its entire contents, features, and functionality (including but not limited to all information, software, text, displays, images, video, and audio, and the design, selection, and arrangement thereof) are owned by the Company, its licensors, or other providers of such material and are protected by United States and international copyright, trademark, patent, trade secret, and other intellectual property or proprietary rights laws.

These Terms of Service permit you to use the Website for your personal, non-commercial use only. You must not reproduce, distribute, modify, create derivative works of, publicly display, publicly perform, republish, download, store, or transmit any of the material on our Website, except as follows:

You must not access or use for any commercial purposes any part of the website or any services or materials available through the Website.

If you print, copy, modify, download, or otherwise use or provide any other person with access to any part of the Website in breach of the Terms of Service, your right to use the Website will stop immediately and you must, at our option, return or destroy any copies of the materials you have made. No right, title, or interest in or to the Website or any content on the Website is transferred to you, and all rights not expressly granted are reserved by the Company. Any use of the Website not expressly permitted by these Terms of Service is a breach of these Terms of Service and may violate copyright, trademark, and other laws.

The Website may provide you with the opportunity to create, submit, post, display, transmit, public, distribute, or broadcast content and materials to us or in the Website, including but not limited to text, writings, video, audio, photographs, graphics, comments, ratings, reviews, feedback, or personal information or other material (collectively, "Content"). You are responsible for your use of the Website and for any content you provide, including compliance with applicable laws, rules, and regulations.

All User Submissions must comply with the Submission Standards and Prohibited Activities set out in these Terms of Service.

Any User Submissions you post to the Website will be considered non-confidential and non-proprietary. By submitting, posting, or displaying content on or through the Website, you grant us a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free license to use, copy, reproduce, process, disclose, adapt, modify, publish, transmit, display and distribute such Content for any purpose, commercial advertising, or otherwise, and to prepare derivative works of, or incorporate in other works, such as Content, and grant and authorize sublicenses of the foregoing. The use and distribution may occur in any media format and through any media channels.

We do not assert any ownership over your Content. You retain full ownership of all of your Content and any intellectual property rights or other proprietary rights associated with your Content. We are not liable for any statement or representations in your Content provided by you in any area in the Website. You are solely responsible for your Content related to the Website and you expressly agree to exonerate us from any and all responsibility and to refrain from any legal action against us regarding your Content. We are not responsible or liable to any third party for the content or accuracy of any User Submissions posted by you or any other user of the Website. User Submissions are not endorsed by us and do not necessarily represent our opinions or the view of any of our affiliates or partners. We do not assume liability for any User Submission or for any claims, liabilities, or losses resulting from any review.

We have the right, in our sole and absolute discretion, (1) to edit, redact, or otherwise change any Content; (2) to recategorize any Content to place them in more appropriate locations in the Website; and (3) to prescreen or delete any Content at any time and for any reason, without notice. We have no obligation to monitor your Content. Any use of the Website in violation of these Terms of Service may result in, among other things, termination or suspension of your right to use the Website.

These Submission Standards apply to any and all User Submissions. User Submissions must in their entirety comply with all the applicable federal, state, local, and international laws and regulations. Without limiting the foregoing, User Submissions must not:

We have the right, without provision of notice to:

You waive and hold harmless company and its parent, subsidiaries, affiliates, and their respective directors, officers, employees, agents, service providers, contractors, licensors, licensees, suppliers, and successors from any and all claims resulting from any action taken by the company and any of the foregoing parties relating to any, investigations by either the company or by law enforcement authorities.

For your convenience, this Website may provide links or pointers to third-party sites or third-party content. We make no representations about any other websites or third-party content that may be accessed from this Website. If you choose to access any such sites, you do so at your own risk. We have no control over the third-party content or any such third-party sites and accept no responsibility for such sites or for any loss or damage that may arise from your use of them. You are subject to any terms and conditions of such third-party sites.

This Website may provide certain social media features that enable you to:

You may use these features solely as they are provided by us and solely with respect to the content they are displayed with. Subject to the foregoing, you must not:

The Website from which you are linking, or on which you make certain content accessible, must comply in all respects with the Submission Standards set out in these Terms of Service.

You agree to cooperate with us in causing any unauthorized framing or linking immediately to stop.

We reserve the right to withdraw linking permission without notice.

We may disable all or any social media features and any links at any time without notice in our discretion.

You understand and agree that your use of the website, its content, and any goods, digital products, services, information or items found or attained through the website is at your own risk. The website, its content, and any goods, services, digital products, information or items found or attained through the website are provided on an "as is" and "as available" basis, without any warranties or conditions of any kind, either express or implied including, but not limited to, the implied warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, or non-infringement. The foregoing does not affect any warranties that cannot be excluded or limited under applicable law.

You acknowledge and agree that company or its respective directors, officers, employees, agents, service providers, contractors, licensors, licensees, suppliers, or successors make no warranty, representation, or endorsement with respect to the completeness, security, reliability, suitability, accuracy, currency, or availability of the website or its contents or that any goods, services, digital products, information or items found or attained through the website will be accurate, reliable, error-free, or uninterrupted, that defects will be corrected, that our website or the server that makes it available or content are free of viruses or other harmful components or destructive code.

Except where such exclusions are prohibited by law, in no event shall the company nor its respective directors, officers, employees, agents, service providers, contractors, licensors, licensees, suppliers, or successors be liable under these terms of service to you or any third-party for any consequential, indirect, incidental, exemplary, special, or punitive damages whatsoever, including any damages for business interruption, loss of use, data, revenue or profit, cost of capital, loss of business opportunity, loss of goodwill, whether arising out of breach of contract, tort (including negligence), any other theory of liability, or otherwise, regardless of whether such damages were foreseeable and whether or not the company was advised of the possibility of such damages.

To the maximum extent permitted by applicable law, you agree to defend, indemnify, and hold harmless Company, its parent, subsidiaries, affiliates, and their respective directors, officers, employees, agents, service providers, contractors, licensors, suppliers, successors, and assigns from and against any claims, liabilities, damages, judgments, awards, losses, costs, expenses, or fees (including reasonable attorneys' fees) arising out of or relating to your breach of these Terms of Service or your use of the Website including, but not limited to, third-party sites and content, any use of the Website's content and services other than as expressly authorized in these Terms of Service or any use of any goods, digital products and information purchased from this Website.

At Company’s sole discretion, it may require you to submit any disputes arising from these Terms of Service or use of the Website, including disputes arising from or concerning their interpretation, violation, invalidity, non-performance, or termination, to final and binding arbitration under the Rules of Arbitration of the American Arbitration Association applying Ontario law. (If multiple jurisdictions, under applicable laws).

Any cause of action or claim you may have arising out of or relating to these terms of use or the website must be commenced within 1 year(s) after the cause of action accrues; otherwise, such cause of action or claim is permanently barred.

Your provision of personal information through the Website is governed by our privacy policy located at the "Privacy Policy".

The Website and these Terms of Service will be governed by and construed in accordance with the laws of the Province of Ontario and any applicable federal laws applicable therein, without giving effect to any choice or conflict of law provision, principle, or rule and notwithstanding your domicile, residence, or physical location. Any action or proceeding arising out of or relating to this Website and/or under these Terms of Service will be instituted in the courts of the Province of Ontario, and each party irrevocably submits to the exclusive jurisdiction of such courts in any such action or proceeding. You waive any and all objections to the exercise of jurisdiction over you by such courts and to the venue of such courts.

If you are a citizen of any European Union country or Switzerland, Norway or Iceland, the governing law and forum shall be the laws and courts of your usual place of residence.

The parties agree that the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods will not govern these Terms of Service or the rights and obligations of the parties under these Terms of Service.

If any provision of these Terms of Service is illegal or unenforceable under applicable law, the remainder of the provision will be amended to achieve as closely as possible the effect of the original term and all other provisions of these Terms of Service will continue in full force and effect.

These Terms of Service constitute the entire and only Terms of Service between the parties in relation to its subject matter and replaces and extinguishes all prior or simultaneous Terms of Services, undertakings, arrangements, understandings or statements of any nature made by the parties or any of them whether oral or written (and, if written, whether or not in draft form) with respect to such subject matter. Each of the parties acknowledges that they are not relying on any statements, warranties or representations given or made by any of them in relation to the subject matter of these Terms of Service, save those expressly set out in these Terms of Service, and that they shall have no rights or remedies with respect to such subject matter otherwise than under these Terms of Service save to the extent that they arise out of the fraud or fraudulent misrepresentation of another party. No variation of these Terms of Service shall be effective unless it is in writing and signed by or on behalf of Company.

No failure to exercise, and no delay in exercising, on the part of either party, any right or any power hereunder shall operate as a waiver thereof, nor shall any single or partial exercise of any right or power hereunder preclude further exercise of that or any other right hereunder.

We may provide any notice to you under these Terms of Service by: (i) sending a message to the email address you provide to us and consent to us using; or (ii) by posting to the Website. Notices sent by email will be effective when we send the email and notices we provide by posting will be effective upon posting. It is your responsibility to keep your email address current.

To give us notice under these Terms of Service, you must contact us as follows: (i) by personal delivery, overnight courier or registered or certified mail to Scry Analytics Inc. 2635 North 1st Street, Suite 200 San Jose, CA 95134, USA. We may update the address for notices to us by posting a notice on this Website. Notices provided by personal delivery will be effective immediately once personally received by an authorized representative of Company. Notices provided by overnight courier or registered or certified mail will be effective once received and where confirmation has been provided to evidence the receipt of the notice.

To request a copy for your information, unsubscribe from our email list, request for your data to be deleted, or ask a question about your data privacy, we've made the process simple: