Transform Your Workflow with Scry AI Automation

Get StartedThe Venture Capital market in India seems to be getting as hot as the country’s famous summers.

However, this potential over-exuberance may lead to some stormy days ahead, based on sobering

research compiled by global research and analytics services firm, Evalueserve.

Evalueserve research shows an interesting phenomenon is beginning to emerge: Over 44 US-based

VC firms are now seeking to invest heavily in start-ups and early-stage companies in India. These

firms have raised, or are in the process of raising, an average of US $100 million each. Indeed, if these

40-plus firms are successful in raising money, they would garner approximately $4.4 billion to be

invested during the next 4 to 5 years. Taking Indian Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) into

consideration, this would be equivalent to $22 billion worth of investment in the US. Since about

$1.75 billion (or approximately 40% of $4.4 billion) has been already raised, even if only $2.2 billion is raised by December 2006, Evalueserve cautions that there will be a glut of VC money for early-

stage investments in India. This will be especially true if the VCs continue to invest only in currently favourite sectors such as IT, BPO, software and hardware products, telecom, and consumer Internet.

Given that a typical start-up in India would require $9 million during the first three years (i.e., $3

million per year) and even assuming that the start-up survives for three years, investing $2.2 billion

during 2007-2010 would imply investing in 150 to 180 start-ups every year during this period, which

simply does not seem practical if the VCs continue to focus only on their current favourite sectors.

In contrast to the emerging trend highlighted above, Indian companies received almost no Private

Equity (PE) or Venture Capital (VC) funding a decade ago. This scenario began to change in the late

1990s with the growth of India’s Information Technology (IT) companies and with the simultaneous

dot-com boom in India. VCs started making large investments in these sectors, however the bust that

followed led to huge losses for the PE and VC community, especially for those who had invested

heavily in start-ups and early stage companies.

After almost three years of downturn in 2001-2003, the PE market began to recover towards the end

of 2004. PE investors began investing in India again, except this time they began investing in other

sectors as well (although the IT and BPO sectors still continued to receive a significant portion of

these investments) and most investments were in late-stage companies. Early-stage investments have

been dwindling or have, at best, remained stagnant right through mid-2006.

Based on Evalueserve’s experience that includes several hundred research engagements focused on

India and the Indian market for our globally dispersed client-base over the last five years, and also

interviews with VCs, Indian entrepreneurs, consultants, and experts within this ecosystem and our

analysis of data from the Indian Venture Capital Association (IVCA) and Venture Intelligence India,

this article examines whether this new, very large total investment can actually be “absorbed” by

start-ups and early-stage companies in India. We will also describe some of the “ground realities” and

highlight a couple of “best practices” that may help VCs to invest more effectively in India.

Note: Most of this article is restricted primarily to early-stage VC investments, i.e.,

investments in a start-up or a small company when the total amount of external money

invested is typically $9 million or less during its entire period of existence. This will be

followed by a separate article, which will focus entirely on Private Equity investments in

India.

1996-1997 – Beginning of PE/VC activity in India: The Indian private equity (PE) and venture

capital (VC) market roughly started in 1996-1997 and it scaled new heights in 2000 primarily because

of the success demonstrated by India in assisting with Y2K related issues as well as the overall boom

in the Information Technology (IT), Telecom and the Internet sectors, which allowed global business

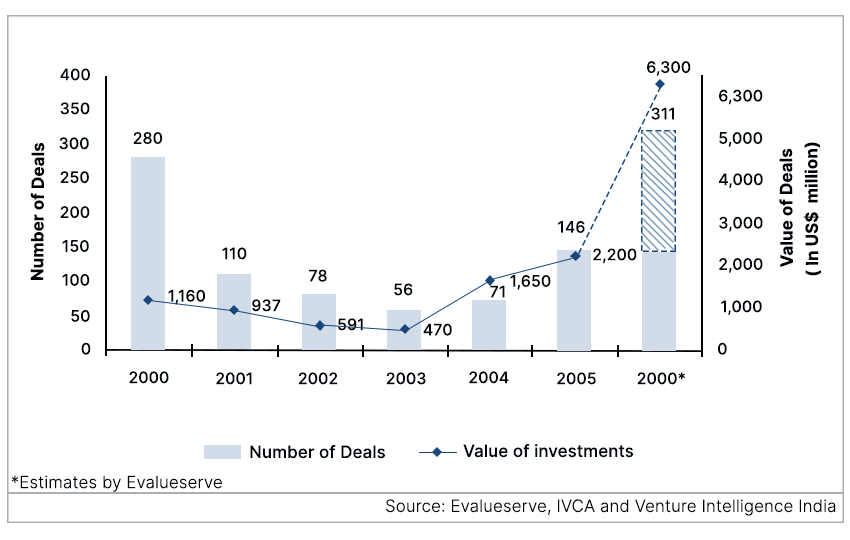

interactions to become much easier. In fact, the total value of such deals done in India in 2000 was

$1.16 billion and the average deal size was approximately US $4.14 million. See Figure 1.

2001-2003 – VC/PE becomes risk averse and activity declines: Not surprisingly, the investing in

India came “crashing down” when NASDAQ lost 60% of its value during the second quarter of 2000

and other public markets (including those in India) also declined substantially. Consequently, during

2001-2003, the VCs and PEs started investing less money and in more mature companies in an effort

to minimize the risks. For example:

2004 onwards – Renewed investor interest and activity: Since India’s economy has been growing at

7%-8% a year, and since some sectors, including the services sector and the high-end manufacturing

sector, have been growing at 12%-14% a year, investors renewed their interest and started investing

again in 2004. As Figure 1 shows, the number of deals and the total dollars invested in India has been

increasing substantially. For example, US $1.65 billion in investments were made in 2004 surpassing

the $1.16 billion in 2000 by almost 42%. These investments reached US $2.2 billion in 2005, and

during the first half of 2006, VCs and PE firms have already invested $3.48 billion (excluding debt

financing). We forecast that the total investment in 2006 is likely to be $6.3 billion, a number that is

more than five times the amount invested in 2000.

Figure 1: Total Number and Value of PE and VC Investments

PE investment expands beyond IT and ITES: A very important feature of the resurgence in the PE

activity in India since 2004 has been that the PEs are no longer focussing only on the IT and the ITES

(IT Enabled Services, commonly known as “Business Process Outsourcing” or BPO) sectors. This is

partly because the growth in the Indian economy is no longer limited to the IT sector but is now

spreading more evenly to sectors such as bio-technology and pharmaceuticals; healthcare and medical

tourism; auto-components; travel and tourism; retail; textiles; real estate and infrastructure;

entertainment and media; and gems and jewellery. Figure 2 shows the division across various sectors

with respect to the number of deals in India in 2000, 2003 and the first half of 2006.

Figure 2: Percentage of the number of deals by PEs in various sectors

| Sectors | 2000 | 2003 | 2006 (Q1&Q2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IT & ITES | 65.5 | 49.1 | 23.18 |

| Financial Services | 3.13 | 12.3 | 9.7 |

| Manufacturing | 3.0 | 1.8 | 19.3 |

| Medical & Healthcare | 2.0 | 7.0 | 8.3 |

| Others | 25.2 | 29.8 | 37.9 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Source: Evalueserve, IVCA and Venture Intelligence India | |||

Since the Purchase Power Parity (PPP) in India is approximately a factor of 5 (as in, a factor of 5 is

used to normalize the GDPs of US & India on a PPP basis), our analysis shows that early stage VC

investments in India should include those that are $8 million or less. In fact, we can classify early-

stage investments further into Seed, Series A and Series B investments depending upon their value.

Figure 3: Investment Range of Early-stage VC Deals in India and the US (in US $)

| Year | India | US |

|---|---|---|

| Seed | Up to $900,000 | Up to $2.5 million |

| Series A | $1 million to $3 million | $3 million to $10 million |

| Series B | $3.5 million to $9 million | $11 million to $30 million |

| Source: Evalueserve | ||

Figure 4 given below provides a break-up of the total value of investments into early-stage

investments (primarily by VCs) and late-stage investments and PIPEs (primarily by PEs). Even within

early-stage investments, seed investments declined the most during 2000-2003 and have essentially

remained negligible during 2004-2006.

Figure 4: Value of Deals (in $ millions) Based on the Type of the Investment

| Year | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 (Q1&Q2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early and Mid Stage VC | 342 | 78 | 81 | 48 | 150 | 103 | 86 |

| Late Stage and PIPEs | 819 | 859 | 510 | 422 | 1,500 | 2,097 | 3,394 |

| Source: Evalueserve, IVCA and Venture Intelligence India | |||||||

Figure 5 shows the break-up of early-stage investments by Seed and Series A and B investments. In a

nuance, perhaps unique to India, after interviewing several entrepreneurs and experts in India, we

believe that since the Indian upper middle class has become quite affluent during the last 7-10 years,

the entrepreneurs are relying more and more on family and friends for seed funding, and since

emerging entrepreneurs come from this upper middle class, the need for seed funding from VCs could

remain low for many years to come!

Figure 5: Number of Early-stage VC Deals

| Year | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seed | 74 | 14 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 5 |

| Series A and B | 68 | 22 | 9 | 8 | 23 | 14 |

| Source: Evalueserve, IVCA and Venture Intelligence India | ||||||

The remaining portion of this article is limited to early-stage VC investments only, i.e.,

investments in a start-up or a small company when the total amount of external money

invested is up to $9 million during its entire period of existence.

Barring occasional forays by VC firms into India in the early to mid-1990s, the first major rush of

VCs to India in recent times was witnessed during the dotcom boom in 1999-2000. However, several

ended up closing shop during 2001-2003 because of the bust that followed. The period 2004-2006 has

seen a resurgence of VC activity. The various VC players operating in India can be broadly classified

as follows:

3.1. Government Funds: Some Indian state government funds are actively investing in India. These

include SIDBI Venture Capital Limited, Gujarat Venture Fund Limited, RVCF, APIDC, Canbank

Venture Capital Fund Limited, IFCI Venture Capital Funds Limited, Rajasthan Asset Management

Co. Private Ltd., KITVEN and Kerala Venture Capital Fund Private Limited. Investments from these

institutions have the advantage of lower ‘cost’ of capital and hence can be more attractive to

entrepreneurs; however, the maximum amount of capital available is typically $500,000.

3.2. Non US-based Funds: These international funds largely invest in early stage and mid stage

companies and include Barings, 2iCapital Private Limited, Aavishkaar India, 3i, (private equity firm

headquartered in Europe), Gaja Capital, Chryscapital Management Companies, HSBC Private Equity

Management (Mauritius) Limited, IL&FS Investments Managers Limited, Information Technology

Venture Enterprises Limited, Indian Direct Equity Advisors Private Limited, Kotak Mahindra Finance

Ltd, Merlion India Fund (Standard Chartered Private Equity), Punjab Venture Capital Limited and

SICOM Capital Management Limited.

3.3. Large Company Funds: For the last 3 to 5 years, many large companies have also been making

early stage and mid-stage VC investments. Such companies are mostly investing in their own

industries and leveraging their expertise with a longer-term view of potential acquisitions. Large

company funds operating in India include those set up by high-tech firms such as Intel, BlueRun

Ventures (owned by Nokia), Motorola, SAP Ventures, Siemens, Acer Technology Ventures, and

Cisco. In addition, several financial companies and a few Indian conglomerates including the

following have small VC funds: Kotak, IDFC, Reliance Capital, JM Financial, Religare (owned by

Ranbaxy), State Bank of India, Banc of America Equity Partners Asia, Unitech (a very large real-

estate developer and manager in India) and Piramal (a well known pharmaceutical company).

3.4. VC Entrants from the US: Evalueserve’s research indicates that several US-based VC funds

have also been investing in the Indian market for the last six years. So far, these funds have been

investing in early and mid-stage technology companies dealing primarily with consumer Internet,

mobile devices, wireless and wire-line, IT services, BPO services, software and hardware products,

electronics and semiconductors. Most of these VC firms are listed in Figure 6.

Figure 6: US-based VC funds investing in India

| Venture Capital Firm | Key Principals | US-India Cross Border & India-based Companies in their Portfolios | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Westbridge (now a part of Sequioa Capital India) |

Sumir Chadha KP Balaraj Surendra K Jain |

AppLabs, Astra, Brainvisa, Celetron, ICICI OneSource, Indecomm, Induslogic, MarketRx, ReaMatrix |

| Sandeep Singhal | Tarang, Zavata, Dr. Lal PathLabs Royal Orchid Hotels, Bharti TeleSoft Mauj, Nazara, Shaadi, Times Internet Travelguru, Emagia, July Systems, Strand Life Sciences, Zenasis |

||

| 2 | Oak Investment Partners | Ranjan Chak | Talisma, Sutherland |

| 3 | Matrix Partners | Shirish Sathaye Avnish Bajaj Rishi Navani |

Not Available |

| 4 | Sherpalo Ventures and Kleiner Perkins, Caufield and Byers, KPCB) |

Ram Sriram Sandeep Murthy Ajit Nazre |

Cleartrip, Paymate, Naukri.com, 247 Customer |

| 5 | The View Group | Mintoo Bhandari | Integreon, Ingenero, TWS, Tracmail, Peerless India |

| 6 | Bessemer Venture Partners |

Rob Chandra | Shriram EPC, Sarovar Hotels & Resorts Rico Auto Industries, Motilal Oswal Financial Services Ltd |

| 8 | Trident Capital | Venetia Kontogouris | Cognizant, Microland, Outsourced

Partners International |

| 9 | Walden International | In process of hiring more Principals after Dinesh Vaswani left |

Headstrong, e4e, InfoTech, Mindtree Venture InfoTek |

| 10 | New Enterprise Associates (NEA) |

Vinod Dham Vani Kola |

IndusLogic, Sasken |

| 11 | Canaan Partners | Deepak Kamra Alok Mittal |

e4e, Bharat Matrimony |

| 12 | Softbank Asia International |

Ravi Adusumalli | SIFY, Slashsupport, Intelligroup, Investmart, MakeMyTrip |

| 13 | International Finance Corporation |

Paul Asel | Indecomm Global Services |

| 14 | Artiman Ventures | Amit Shah Yatin Mundkur M.J. Aravind Saurabh Srivastava |

BioImagine, Net Devices, Opsource |

| 15 | Columbia Capital | Hemant Kanakia Arun Gupta |

Net Devices, Approva |

| 16 | Gabriel Venture Partners | Navin Chaddha | Allsec, IL&FS Investsmart,

MakeMyTrip, Persistent Systems, Tejas |

| 17 | Norwest Venture Partners | Pramod Haque Vab Goel |

Persistent Systems, Yatra |

| 18 | Austin Ventures | Venu Shamapant Krishna Srinivasan |

Siperia |

| 19 | Sigma Partners | Mark Pine | Emagia Solutions, Kirusa, Zenasis

Technologies, Virtusa |

| 20 | Charles River Ventures | Izhar Armony | July Systems, Virtusa, Net Customer |

| 21 | Financial Technology Ventures |

Eric Byunn | Exlservice |

| 22 | Telesoft Partners | Arjun Gupta Santhil Durairal |

Bombay Cellular |

| 23 | Draper, Fisher, Jurvetson | Raj Atluru | Personiva (f.k.a, Pictureal)

Seventymm |

| 24 | Sierra Ventures | Vispi Daver Tm Guleri |

Everest Software, Astra Business Services, Approva, Razorsight |

| 25 | Battery Ventures | Mark Sherman | Tejas Networks |

3.5. New Groups Raising Money for Investing in India: In addition to the US-based VC groups that

have already invested in cross-border start-ups and in “pure” India-based companies, and excluding

US-based PE firms (e.g., Francisco Partners, Texas Pacific Group, General Atlantic Partners,

Warburg Pincus, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co.) that are likely to make late-stage investments or

PIPEs, our research shows that more than 19 other groups are raising – or have raised – money to

establish funds in India. These groups are primarily US-based VCs, usually with Non-Resident

Indians who are based in the US, who have by and large not made any investments in India. These 19

groups do not include some well known US-based funds (e.g., Greylock and Mayfield) that are in the

process of formulating an “investing strategy for India.” Since some groups have requested anonymity

and confidentiality because they are still in the process of raising money, only 14 out of 19 are

mentioned below:

3.6. Future of Early Stage Investments in India: In summary, our research shows that there are

more than 44 VC groups that have either already raised — or are in the process of raising — between

$40 and $400 million for early-stage investments in Indian companies. If all these groups were

successful in raising money, then jointly they would raise $4.4 billion (i.e., an average size of $100

million per fund) that would need to be invested during the next 4-5 years. Considering the Purchase

Power Parity (PPP) in India is approximately 5, this is equivalent to investing around $22 billion in

the US, which is really large no matter the geography! Since about $1.75 billion (or approximately

40% of $4.4 billion) has already been raised, if we assume just half of this money (i.e., $2.2 billion) is

eventually raised, it would clearly result in a glut of VC money for early-stage and mid-stage

investments in India, especially true if the VCs continue to invest only in currently favourite sectors

such as IT, BPO, software and hardware products, telecom, and consumer Internet.

Given that a typical start-up in India would require $9 million during the first three years (i.e., $3

million per year), and assuming that the start-up in fact survives for three years, investing $2.2 billion

during 2007-2010 would imply investing in 150 to 180 start-ups every year during this period, which would simply not be possible if the VCs continue to focus on their current favourite sectors. This, of

course, would be a marked contrast to the current situation in India (wherein such funding is rather

scarce) and it will also make the market for the ‘right deals’ extremely competitive for these VCs.

Keeping this in view, in the next section, we analyze some of the on-the-ground realities and best

practices for VCs to invest effectively in India.

In many respects, the sophistication and maturity of VC investments in India today are probably at the

same level as in the early 1970s in the US. This section advocates some “best practices” and

highlights some of the key differences between investing in early-stage and mid-stage companies in

the US versus investing in similar companies in India.

4.1. Maniacal focus on early profitability might be counter-productive for a product company: Unlike most start-ups in the US, which are usually product-based and are usually expecting 2-3 stages

of investment, entrepreneurs in India are usually focussed on making their companies profitable as

soon as possible. This mindset might be because Indian entrepreneurs have, to some extent,

traditionally founded services and trading companies. From an Indian entrepreneur’s perspective, the

reasons for making their company profitable quickly include: (a) the scarcity of available venture

capital in India so far, (b) reluctance in giving up too much equity, and (c) since most Indian start-ups

have been in the service sector so far, they require a significantly smaller amount of venture capital.

Of course, the disadvantages of such a maniacal focus on profitability include (a) the possibility that

an Indian start-up may not able to grow very quickly or realize its full potential and (b) the possibility

of an Indian start-up being upstaged by some other firm somewhere else in the world. Hence, the VCs

must play a crucial role in educating Indian entrepreneurs to think differently in the context of

product-based companies compared to how they have traditionally run their companies.

4.2. Need for continued funding but in small amounts: Since the Purchase Power Parity in India is

5, and since many – if not most – Indian start-ups still continue to be created in the services business,

and since the entrepreneurs for even those product-based start-ups wish to achieve profitability

quickly, we believe the VCs should not look at funding Indian companies in distinct stages (i.e., seed

funding, Stage A funding, Stage B funding, mezzanine funding etc). Rather they should provide small

portions of “continuous” funding based on continued attainment of predefined metrics such as

revenues, profits, development expenses, etc. Of course, this would imply that the VC has to be more

involved operationally with the Indian start-up and simply attending a board meeting every two or

three months might not be sufficient. It would also imply that the VC would essentially act as a

“bank” that provides money in exchange for equity, as and when needed.

4.3. Indian entrepreneurs lack marketing, sales and business development expertise: During our

interviews and research, we found Indian entrepreneurs to be quite adept technically and definitely at

par with similar entrepreneurs in developed countries. However, we also found the entrepreneurs in

India generally lacked expertise in marketing, sales and business development areas, especially when

compared to their counterparts in the US. Furthermore, since India had socialistic economic policies

during 1947-1992, there is a lack of good talent in marketing and sales professionals who can thrive in

an extremely competitive environment. Hence, finding the appropriate marketing, sales and business

development people is one area where Indian start-ups need help. This problem is further exacerbated

because the Indian economy has been growing at 8% and most start-ups have to compete for talent not

only with other companies who are exporting similar or dissimilar products and services but also with

many Indian domestic companies. In fact, finding and retaining the ‘right talent’ has become an issue

not only in marketing, sales and business development but also in research, technical and advanced

development areas. Finally, if the eventual market were a developed country, then such expertise can

be potentially found in that country. However, if the market for the corresponding product or service

is India, China or some other developing nation, then finding such people can be a Herculean task!

4.4. Indian entrepreneurs are hesitant to give up control: Indian entrepreneurs are usually hesitant about giving up control. In fact, most of the entrepreneurs in India currently receive their initial 8 funding from family and friends, and even if they do not do so, the Indian social system is such that

relatives and friends still end up being a major influence. Also, since the Bombay Stock Exchange

(BSE) has been growing quite rapidly (in spite of the recent 20% drop) and a company with $20

million in annual revenue can be easily listed on it, many Indian entrepreneurs would rather list their

companies on BSE than give up a substantial share to the VCs. Consequently, the VCs will have to

provide a very clear value proposition to the start-ups and cannot simply state that they bring value to

the table just because they are well connected, etc. In fact, we believe that in some cases the VCs may

even have to go to the extreme of closing contracts and bringing in the revenue on behalf of a start-up

rather than simply “opening doors” by providing the contacts in their “Rolodex.”

4.5. Lack of financial transparency and other processes: Again, partly because the Indian economy

was a “socialistic and closed” economy and partly because Indian entrepreneurs are not as proficient

at business development as their counterparts in the US, Indian start-ups lack financial transparency

and often have limited experience in implementing effective financial processes. This usually makes

the task of the VC much more difficult not only during the due-diligence phase, but also in helping the

start-up grow rapidly. Consequently, we believe that immediately after making its investment, the VC

may have to “roll up the sleeves” and help the entrepreneurs in “process-izing” the company. We also

believe that simply directing the Indian entrepreneurs to implement processes during monthly or

quarterly board meetings may prove to be futile because many entrepreneurs might not know how to

execute on these instructions.

4.6. Investment thesis and the current model is un-sustainable: One of the most worrisome aspects

of the VCs’ new-found zeal to invest in India is that most VCs want to continue to invest in Indian

start-ups in areas they are most familiar with, i.e., in IT, telecom and Internet products and services.

So, it is not surprising that eight consumer-travel Internet websites have already been funded in India,

and given that this sector only accounted for approximately $152 million worth of booking

transactions in 2005, and given that this number is likely to grow to only to $1.2 billion by 2010, the

actual revenue and profits earned by this sector even in 2010 are likely to be $75 million and $9

million respectively, which is miniscule by any standards! Similarly, if we study the cross-border and

“pure” India-based companies listed in Section 2.4, more than 90% are in the IT, ITES and BPO,

Telecom, and Consumer Internet.

So, going forward, the VCs may want to investigate the following rapidly emerging sectors for

potential investment: auto-components, travel and tourism, domestic healthcare and medical tourism,

retail, textiles, biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, real estate and infrastructure, entertainment and

media, gems and jewellery, and of course, the traditional sectors that include telecom, IT, and

Business Process Outsourcing services. An overview of these sectors has been provided in a separate

research paper from Evalueserve.

Finally, it is interesting to note that in this regard, several VC firms (e.g., ChrysCapital, Westbridge –

now a part of Sequoia Capital, India) are beginning to follow a well-rounded and diversified strategy,

but so far most of it is limited to late stage investments and PIPEs. For example, during the last 2-3

years, Bessemer has invested in the following companies:

4.7. Lack of VCs who have cross-border experience: The other really worrisome aspect is that many

US-based VCs believe they can help the growth of Indian start-ups, and provide good returns to their

own shareholders by:

4.8. Well-known US VCs may not have the same brand recognition in India yet: Since venture

capital investing in India is a relatively recent phenomenon, VCs who may be well known in the US

may not yet be able to take their brand recognition in India for granted. In fact, we believe that

successful Indian entrepreneurs and VCs who have lived in the US and have at least ten years of

experience in running their own companies, or have been actively involved in helping others and can

get down in the “trenches” with the Indian entrepreneurs are more likely to succeed and build a brand-

name for themselves and their groups. Of course, on the other hand, since most – if not all – of these

groups are raising the money in the US, brand name VCs in the US will definitely be able to raise this

money much more efficiently and effectively than those groups that are not known in the US. Again,

the implication for the VC firm is that it will have to articulate a very clear value proposition.

At Scry Analytics Inc ("us", "we", "our" or the "Company") we value your privacy and the importance of safeguarding your data. This Privacy Policy (the "Policy") describes our privacy practices for the activities set out below. As per your rights, we inform you how we collect, store, access, and otherwise process information relating to individuals. In this Policy, personal data (“Personal Data”) refers to any information that on its own, or in combination with other available information, can identify an individual.

We are committed to protecting your privacy in accordance with the highest level of privacy regulation. As such, we follow the obligations under the below regulations:

This policy applies to the Scry Analytics, Inc. websites, domains, applications, services, and products.

This Policy does not apply to third-party applications, websites, products, services or platforms that may be accessed through (non-) links that we may provide to you. These sites are owned and operated independently from us, and they have their own separate privacy and data collection practices. Any Personal Data that you provide to these websites will be governed by the third-party’s own privacy policy. We cannot accept liability for the actions or policies of these independent sites, and we are not responsible for the content or privacy practices of such sites.

This Policy applies when you interact with us by doing any of the following:

What Personal Data We Collect

When attempt to contact us or make a purchase, we collect the following types of Personal Data:

This includes:

Account Information such as your name, email address, and password

Automated technologies or interactions: As you interact with our website, we may automatically collect the following types of data (all as described above): Device Data about your equipment, Usage Data about your browsing actions and patterns, and Contact Data where tasks carried out via our website remain uncompleted, such as incomplete orders or abandoned baskets. We collect this data by using cookies, server logs and other similar technologies. Please see our Cookie section (below) for further details.

If you provide us, or our service providers, with any Personal Data relating to other individuals, you represent that you have the authority to do so and acknowledge that it will be used in accordance with this Policy. If you believe that your Personal Data has been provided to us improperly, or to otherwise exercise your rights relating to your Personal Data, please contact us by using the information set out in the “Contact us” section below.

When you visit a Scry Analytics, Inc. website, we automatically collect and store information about your visit using browser cookies (files which are sent by us to your computer), or similar technology. You can instruct your browser to refuse all cookies or to indicate when a cookie is being sent. The Help Feature on most browsers will provide information on how to accept cookies, disable cookies or to notify you when receiving a new cookie. If you do not accept cookies, you may not be able to use some features of our Service and we recommend that you leave them turned on.

We also process information when you use our services and products. This information may include:

We may receive your Personal Data from third parties such as companies subscribing to Scry Analytics, Inc. services, partners and other sources. This Personal Data is not collected by us but by a third party and is subject to the relevant third party’s own separate privacy and data collection policies. We do not have any control or input on how your Personal Data is handled by third parties. As always, you have the right to review and rectify this information. If you have any questions you should first contact the relevant third party for further information about your Personal Data.

Our websites and services may contain links to other websites, applications and services maintained by third parties. The information practices of such other services, or of social media networks that host our branded social media pages, are governed by third parties’ privacy statements, which you should review to better understand those third parties’ privacy practices.

We collect and use your Personal Data with your consent to provide, maintain, and develop our products and services and understand how to improve them.

These purposes include:

Where we process your Personal Data to provide a product or service, we do so because it is necessary to perform contractual obligations. All of the above processing is necessary in our legitimate interests to provide products and services and to maintain our relationship with you and to protect our business for example against fraud. Consent will be required to initiate services with you. New consent will be required if any changes are made to the type of data collected. Within our contract, if you fail to provide consent, some services may not be available to you.

Where possible, we store and process data on servers within the general geographical region where you reside (note: this may not be within the country in which you reside). Your Personal Data may also be transferred to, and maintained on, servers residing outside of your state, province, country or other governmental jurisdiction where the data laws may differ from those in your jurisdiction. We will take appropriate steps to ensure that your Personal Data is treated securely and in accordance with this Policy as well as applicable data protection law.Data may be kept in other countries that are considered adequate under your laws.

We will share your Personal Data with third parties only in the ways set out in this Policy or set out at the point when the Personal Data is collected.

We also use Google Analytics to help us understand how our customers use the site. You can read more about how Google uses your Personal Data here: Google Privacy Policy

You can also opt-out of Google Analytics here: https://tools.google.com/dlpage/gaoptout

We may use or disclose your Personal Data in order to comply with a legal obligation, in connection with a request from a public or government authority, or in connection with court or tribunal proceedings, to prevent loss of life or injury, or to protect our rights or property. Where possible and practical to do so, we will tell you in advance of such disclosure.

We may use a third party service provider, independent contractors, agencies, or consultants to deliver and help us improve our products and services. We may share your Personal Data with marketing agencies, database service providers, backup and disaster recovery service providers, email service providers and others but only to maintain and improve our products and services. For further information on the recipients of your Personal Data, please contact us by using the information in the “Contacting us” section below.

A cookie is a small file with information that your browser stores on your device. Information in this file is typically shared with the owner of the site in addition to potential partners and third parties to that business. The collection of this information may be used in the function of the site and/or to improve your experience.

To give you the best experience possible, we use the following types of cookies: Strictly Necessary. As a web application, we require certain necessary cookies to run our service.

We use preference cookies to help us remember the way you like to use our service. Some cookies are used to personalize content and present you with a tailored experience. For example, location could be used to give you services and offers in your area. Analytics. We collect analytics about the types of people who visit our site to improve our service and product.

So long as the cookie is not strictly necessary, you may opt in or out of cookie use at any time. To alter the way in which we collect information from you, visit our Cookie Manager.

A cookie is a small file with information that your browser stores on your device. Information in this file is typically shared with the owner of the site in addition to potential partners and third parties to that business. The collection of this information may be used in the function of the site and/or to improve your experience.

So long as the cookie is not strictly necessary, you may opt in or out of cookie use at any time. To alter the way in which we collect information from you, visit our Cookie Manager.

We will only retain your Personal Data for as long as necessary for the purpose for which that data was collected and to the extent required by applicable law. When we no longer need Personal Data, we will remove it from our systems and/or take steps to anonymize it.

If we are involved in a merger, acquisition or asset sale, your personal information may be transferred. We will provide notice before your personal information is transferred and becomes subject to a different Privacy Policy. Under certain circumstances, we may be required to disclose your personal information if required to do so by law or in response to valid requests by public authorities (e.g. a court or a government agency).

We have appropriate organizational safeguards and security measures in place to protect your Personal Data from being accidentally lost, used or accessed in an unauthorized way, altered or disclosed. The communication between your browser and our website uses a secure encrypted connection wherever your Personal Data is involved. We require any third party who is contracted to process your Personal Data on our behalf to have security measures in place to protect your data and to treat such data in accordance with the law. In the unfortunate event of a Personal Data breach, we will notify you and any applicable regulator when we are legally required to do so.

We do not knowingly collect Personal Data from children under the age of 18 Years.

Depending on your geographical location and citizenship, your rights are subject to local data privacy regulations. These rights may include:

Right to Access (PIPEDA, GDPR Article 15, CCPA/CPRA, CPA, VCDPA, CTDPA, UCPA, LGPD, POPIA)

You have the right to learn whether we are processing your Personal Data and to request a copy of the Personal Data we are processing about you.

Right to Rectification (PIPEDA, GDPR Article 16, CPRA, CPA, VCDPA, CTDPA, LGPD, POPIA)

You have the right to have incomplete or inaccurate Personal Data that we process about you rectified.

Right to be Forgotten (right to erasure) (GDPR Article 17, CCPA/CPRA, CPA, VCDPA, CTDPA, UCPA, LGPD, POPIA)

You have the right to request that we delete Personal Data that we process about you, unless we need to retain such data in order to comply with a legal obligation or to establish, exercise or defend legal claims.

Right to Restriction of Processing (GDPR Article 18, LGPD)

You have the right to restrict our processing of your Personal Data under certain circumstances. In this case, we will not process your Data for any purpose other than storing it.

Right to Portability (PIPEDA, GDPR Article 20, LGPD)

You have the right to obtain Personal Data we hold about you, in a structured, electronic format, and to transmit such Personal Data to another data controller, where this is (a) Personal Data which you have provided to us, and (b) if we are processing that data on the basis of your consent or to perform a contract with you or the third party that subscribes to services.

Right to Opt Out (CPRA, CPA, VCDPA, CTDPA, UCPA)

You have the right to opt out of the processing of your Personal Data for purposes of: (1) Targeted advertising; (2) The sale of Personal Data; and/or (3) Profiling in furtherance of decisions that produce legal or similarly significant effects concerning you. Under CPRA, you have the right to opt out of the sharing of your Personal Data to third parties and our use and disclosure of your Sensitive Personal Data to uses necessary to provide the products and services reasonably expected by you.

Right to Objection (GDPR Article 21, LGPD, POPIA)

Where the legal justification for our processing of your Personal Data is our legitimate interest, you have the right to object to such processing on grounds relating to your particular situation. We will abide by your request unless we have compelling legitimate grounds for processing which override your interests and rights, or if we need to continue to process the Personal Data for the establishment, exercise or defense of a legal claim.

Nondiscrimination and nonretaliation (CCPA/CPRA, CPA, VCDPA, CTDPA, UCPA)

You have the right not to be denied service or have an altered experience for exercising your rights.

File an Appeal (CPA, VCDPA, CTDPA)

You have the right to file an appeal based on our response to you exercising any of these rights. In the event you disagree with how we resolved the appeal, you have the right to contact the attorney general located here:

If you are based in Colorado, please visit this website to file a complaint. If you are based in Virginia, please visit this website to file a complaint. If you are based in Connecticut, please visit this website to file a complaint.

File a Complaint (GDPR Article 77, LGPD, POPIA)

You have the right to bring a claim before their competent data protection authority. If you are based in the EEA, please visit this website (http://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/article29/document.cfm?action=display&doc_id=50061) for a list of local data protection authorities.

If you have consented to our processing of your Personal Data, you have the right to withdraw your consent at any time, free of charge, such as where you wish to opt out from marketing messages that you receive from us. If you wish to withdraw your consent, please contact us using the information found at the bottom of this page.

You can make a request to exercise any of these rights in relation to your Personal Data by sending the request to our privacy team by using the form below.

For your own privacy and security, at our discretion, we may require you to prove your identity before providing the requested information.

We may modify this Policy at any time. If we make changes to this Policy then we will post an updated version of this Policy at this website. When using our services, you will be asked to review and accept our Privacy Policy. In this manner, we may record your acceptance and notify you of any future changes to this Policy.

To request a copy for your information, unsubscribe from our email list, request for your data to be deleted, or ask a question about your data privacy, we've made the process simple:

Our aim is to keep this Agreement as readable as possible, but in some cases for legal reasons, some of the language is required "legalese".

These terms of service are entered into by and between You and Scry Analytics, Inc., ("Company," "we," "our," or "us"). The following terms and conditions, together with any documents they expressly incorporate by reference (collectively "Terms of Service"), govern your access to and use of www.scryai.com, including any content, functionality, and services offered on or through www.scryai.com (the "Website").

Please read the Terms of Service carefully before you start to use the Website.

By using the Website [or by clicking to accept or agree to the Terms of Service when this option is made available to you], you accept and agree to be bound and abide by these Terms of Service and our Privacy Policy, found at Privacy Policy, incorporated herein by reference. If you do not want to agree to these Terms of Service, you must not access or use the Website.

Accept and agree to be bound and comply with these terms of service. You represent and warrant that you are the legal age of majority under applicable law to form a binding contract with us and, you agree if you access the website from a jurisdiction where it is not permitted, you do so at your own risk.

We may revise and update these Terms of Service from time to time in our sole discretion. All changes are effective immediately when we post them and apply to all access to and use of the Website thereafter.

Continuing to use the Website following the posting of revised Terms of Service means that you accept and agree to the changes. You are expected to check this page each time you access this Website so you are aware of any changes, as they are binding on you.

You are required to ensure that all persons who access the Website are aware of this Agreement and comply with it. It is a condition of your use of the Website that all the information you provide on the Website is correct, current, and complete.

You are solely and entirely responsible for your use of the website and your computer, internet and data security.

You may use the Website only for lawful purposes and in accordance with these Terms of Service. You agree not to use the Website:

The Website and its entire contents, features, and functionality (including but not limited to all information, software, text, displays, images, video, and audio, and the design, selection, and arrangement thereof) are owned by the Company, its licensors, or other providers of such material and are protected by United States and international copyright, trademark, patent, trade secret, and other intellectual property or proprietary rights laws.

These Terms of Service permit you to use the Website for your personal, non-commercial use only. You must not reproduce, distribute, modify, create derivative works of, publicly display, publicly perform, republish, download, store, or transmit any of the material on our Website, except as follows:

You must not access or use for any commercial purposes any part of the website or any services or materials available through the Website.

If you print, copy, modify, download, or otherwise use or provide any other person with access to any part of the Website in breach of the Terms of Service, your right to use the Website will stop immediately and you must, at our option, return or destroy any copies of the materials you have made. No right, title, or interest in or to the Website or any content on the Website is transferred to you, and all rights not expressly granted are reserved by the Company. Any use of the Website not expressly permitted by these Terms of Service is a breach of these Terms of Service and may violate copyright, trademark, and other laws.

The Website may provide you with the opportunity to create, submit, post, display, transmit, public, distribute, or broadcast content and materials to us or in the Website, including but not limited to text, writings, video, audio, photographs, graphics, comments, ratings, reviews, feedback, or personal information or other material (collectively, "Content"). You are responsible for your use of the Website and for any content you provide, including compliance with applicable laws, rules, and regulations.

All User Submissions must comply with the Submission Standards and Prohibited Activities set out in these Terms of Service.

Any User Submissions you post to the Website will be considered non-confidential and non-proprietary. By submitting, posting, or displaying content on or through the Website, you grant us a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free license to use, copy, reproduce, process, disclose, adapt, modify, publish, transmit, display and distribute such Content for any purpose, commercial advertising, or otherwise, and to prepare derivative works of, or incorporate in other works, such as Content, and grant and authorize sublicenses of the foregoing. The use and distribution may occur in any media format and through any media channels.

We do not assert any ownership over your Content. You retain full ownership of all of your Content and any intellectual property rights or other proprietary rights associated with your Content. We are not liable for any statement or representations in your Content provided by you in any area in the Website. You are solely responsible for your Content related to the Website and you expressly agree to exonerate us from any and all responsibility and to refrain from any legal action against us regarding your Content. We are not responsible or liable to any third party for the content or accuracy of any User Submissions posted by you or any other user of the Website. User Submissions are not endorsed by us and do not necessarily represent our opinions or the view of any of our affiliates or partners. We do not assume liability for any User Submission or for any claims, liabilities, or losses resulting from any review.

We have the right, in our sole and absolute discretion, (1) to edit, redact, or otherwise change any Content; (2) to recategorize any Content to place them in more appropriate locations in the Website; and (3) to prescreen or delete any Content at any time and for any reason, without notice. We have no obligation to monitor your Content. Any use of the Website in violation of these Terms of Service may result in, among other things, termination or suspension of your right to use the Website.

These Submission Standards apply to any and all User Submissions. User Submissions must in their entirety comply with all the applicable federal, state, local, and international laws and regulations. Without limiting the foregoing, User Submissions must not:

We have the right, without provision of notice to:

You waive and hold harmless company and its parent, subsidiaries, affiliates, and their respective directors, officers, employees, agents, service providers, contractors, licensors, licensees, suppliers, and successors from any and all claims resulting from any action taken by the company and any of the foregoing parties relating to any, investigations by either the company or by law enforcement authorities.

For your convenience, this Website may provide links or pointers to third-party sites or third-party content. We make no representations about any other websites or third-party content that may be accessed from this Website. If you choose to access any such sites, you do so at your own risk. We have no control over the third-party content or any such third-party sites and accept no responsibility for such sites or for any loss or damage that may arise from your use of them. You are subject to any terms and conditions of such third-party sites.

This Website may provide certain social media features that enable you to:

You may use these features solely as they are provided by us and solely with respect to the content they are displayed with. Subject to the foregoing, you must not:

The Website from which you are linking, or on which you make certain content accessible, must comply in all respects with the Submission Standards set out in these Terms of Service.

You agree to cooperate with us in causing any unauthorized framing or linking immediately to stop.

We reserve the right to withdraw linking permission without notice.

We may disable all or any social media features and any links at any time without notice in our discretion.

You understand and agree that your use of the website, its content, and any goods, digital products, services, information or items found or attained through the website is at your own risk. The website, its content, and any goods, services, digital products, information or items found or attained through the website are provided on an "as is" and "as available" basis, without any warranties or conditions of any kind, either express or implied including, but not limited to, the implied warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, or non-infringement. The foregoing does not affect any warranties that cannot be excluded or limited under applicable law.

You acknowledge and agree that company or its respective directors, officers, employees, agents, service providers, contractors, licensors, licensees, suppliers, or successors make no warranty, representation, or endorsement with respect to the completeness, security, reliability, suitability, accuracy, currency, or availability of the website or its contents or that any goods, services, digital products, information or items found or attained through the website will be accurate, reliable, error-free, or uninterrupted, that defects will be corrected, that our website or the server that makes it available or content are free of viruses or other harmful components or destructive code.

Except where such exclusions are prohibited by law, in no event shall the company nor its respective directors, officers, employees, agents, service providers, contractors, licensors, licensees, suppliers, or successors be liable under these terms of service to you or any third-party for any consequential, indirect, incidental, exemplary, special, or punitive damages whatsoever, including any damages for business interruption, loss of use, data, revenue or profit, cost of capital, loss of business opportunity, loss of goodwill, whether arising out of breach of contract, tort (including negligence), any other theory of liability, or otherwise, regardless of whether such damages were foreseeable and whether or not the company was advised of the possibility of such damages.

To the maximum extent permitted by applicable law, you agree to defend, indemnify, and hold harmless Company, its parent, subsidiaries, affiliates, and their respective directors, officers, employees, agents, service providers, contractors, licensors, suppliers, successors, and assigns from and against any claims, liabilities, damages, judgments, awards, losses, costs, expenses, or fees (including reasonable attorneys' fees) arising out of or relating to your breach of these Terms of Service or your use of the Website including, but not limited to, third-party sites and content, any use of the Website's content and services other than as expressly authorized in these Terms of Service or any use of any goods, digital products and information purchased from this Website.

At Company’s sole discretion, it may require you to submit any disputes arising from these Terms of Service or use of the Website, including disputes arising from or concerning their interpretation, violation, invalidity, non-performance, or termination, to final and binding arbitration under the Rules of Arbitration of the American Arbitration Association applying Ontario law. (If multiple jurisdictions, under applicable laws).

Any cause of action or claim you may have arising out of or relating to these terms of use or the website must be commenced within 1 year(s) after the cause of action accrues; otherwise, such cause of action or claim is permanently barred.

Your provision of personal information through the Website is governed by our privacy policy located at the "Privacy Policy".

The Website and these Terms of Service will be governed by and construed in accordance with the laws of the Province of Ontario and any applicable federal laws applicable therein, without giving effect to any choice or conflict of law provision, principle, or rule and notwithstanding your domicile, residence, or physical location. Any action or proceeding arising out of or relating to this Website and/or under these Terms of Service will be instituted in the courts of the Province of Ontario, and each party irrevocably submits to the exclusive jurisdiction of such courts in any such action or proceeding. You waive any and all objections to the exercise of jurisdiction over you by such courts and to the venue of such courts.

If you are a citizen of any European Union country or Switzerland, Norway or Iceland, the governing law and forum shall be the laws and courts of your usual place of residence.

The parties agree that the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods will not govern these Terms of Service or the rights and obligations of the parties under these Terms of Service.

If any provision of these Terms of Service is illegal or unenforceable under applicable law, the remainder of the provision will be amended to achieve as closely as possible the effect of the original term and all other provisions of these Terms of Service will continue in full force and effect.

These Terms of Service constitute the entire and only Terms of Service between the parties in relation to its subject matter and replaces and extinguishes all prior or simultaneous Terms of Services, undertakings, arrangements, understandings or statements of any nature made by the parties or any of them whether oral or written (and, if written, whether or not in draft form) with respect to such subject matter. Each of the parties acknowledges that they are not relying on any statements, warranties or representations given or made by any of them in relation to the subject matter of these Terms of Service, save those expressly set out in these Terms of Service, and that they shall have no rights or remedies with respect to such subject matter otherwise than under these Terms of Service save to the extent that they arise out of the fraud or fraudulent misrepresentation of another party. No variation of these Terms of Service shall be effective unless it is in writing and signed by or on behalf of Company.

No failure to exercise, and no delay in exercising, on the part of either party, any right or any power hereunder shall operate as a waiver thereof, nor shall any single or partial exercise of any right or power hereunder preclude further exercise of that or any other right hereunder.

We may provide any notice to you under these Terms of Service by: (i) sending a message to the email address you provide to us and consent to us using; or (ii) by posting to the Website. Notices sent by email will be effective when we send the email and notices we provide by posting will be effective upon posting. It is your responsibility to keep your email address current.

To give us notice under these Terms of Service, you must contact us as follows: (i) by personal delivery, overnight courier or registered or certified mail to Scry Analytics Inc. 2635 North 1st Street, Suite 200 San Jose, CA 95134, USA. We may update the address for notices to us by posting a notice on this Website. Notices provided by personal delivery will be effective immediately once personally received by an authorized representative of Company. Notices provided by overnight courier or registered or certified mail will be effective once received and where confirmation has been provided to evidence the receipt of the notice.

To request a copy for your information, unsubscribe from our email list, request for your data to be deleted, or ask a question about your data privacy, we've made the process simple: